Saving the Bell's turtle

Each year, almost 100 percent of Bell’s turtle nests are raided by foxes, putting them at high risk of extinction.

So, with turtle nesting season well and truly upon us, what can we do to help protect this threatened native species?

We had a chat with UNE PhD candidate, Lou Streeting, to find out more about the Bell’s turtle, what the general public can do to help, and some of the important work currently underway to save the species.

What are Bell's turtles and why do they need protecting?

The Western Saw-Shelled turtle, otherwise known as the Bell’s turtle, is an endangered freshwater species found in the high-altitude rivers of the New England Tablelands.

They're not found anywhere else in the world.

With foxes raiding almost 100 percent of nests, the Bell’s turtle population is at a high risk of extinction due to the low number of juveniles living in the wild.

This means the population is ageing too quickly, and the number of turtles able to reproduce is dwindling at an alarming rate.

Luckily, researchers like UNE PhD Candidate Louise Streeting, are working hard to give the population a needed boost.

“The Turtles Forever conservation program has been protecting Bell’s turtle nests from fox predation for over six years now,” says Lou.

“The first nests were protected as part of my PhD project, and now Turtles Forever is continuing this conservation action.”

Turtles Forever protect nests individually using wire mesh and by erecting temporary fox exclusion fences around prime Bell’s turtle nesting habitat.

“These measures have been super effective, and the fences have the bonus of protecting the females and hatchling turtles from fox predation as well.”

Hatchlings emerging from a nest that has been protected by wire mesh.

In addition, Lou and others at UNE are collaborating with the Northern Tablelands Local Land Services to produce hatchlings that can be released back into the waterways.

This year, Lou and the team incubated and hatched a whopping 1500 turtle eggs in a lab on the UNE campus.

These were then released back into the local waterways to supplement the wild juvenile population.

“This project has been going for six years now, but this was the largest number of hatchlings that we’ve produced so far," says Lou.

"We’re hoping that in two to three years’ time, these turtles will be showing up in our surveys, and we’ll be seeing that they’re surviving and thriving in the wild.”

Another aspect of Lou’s PhD project has been to track hatchlings and their movements.

“As part of my PhD, I tracked Bell’s turtle hatchlings and identified that hatchlings sheltered in the vegetated margins of pools and dispersed through flowing vegetated riffles and rivulets," says Lou.

“Hatchlings moved both up and downstream for up to two kilometres in just over two weeks, but always remained within the vegetation lining the river’s edge.

"This means that when water levels drop below the fringing vegetation, hatchlings are left exposed to predation in open water.

"So minimal flows between February and April are important as they provide the shelter and connectivity that young turtles need to survive and move between habitats.”

Recently, some of Lou’s findings were published by the NSW Department of Planning and Environment in a document titled Turtles and Flows, and will contribute to the development of water management policies which aim to protect minimum river flows crucial for maintaining Bell’s turtle habitats.

“The draft plan is on public exhibition until 17th December, and I hope that my research will help people to provide an informed response to the draft plan and highlight the crucial need to preserve the minimal flows necessary for ensuring this species' long-term survival."

What can we do to help?

You don’t need to be a conservationist working in the lab or out in the field to help save the Bell’s turtle.

“We can all team up to help our turtles! If you have Bell’s turtles on your property and would like to know how you can protect their nests from fox predation, reach out to us here."

For everyone else, citizen science projects, such as the 1 Million Turtles project, is one way to do your bit for the species.

“The 1 Million Turtles project is asking the community to get involved in turtle nest protection activities and to report sightings of turtles and turtle nesting activity to help build a nest predictor tool.”

1 Million Turtles is an award-winning collaboration between researchers from the University of New England (UNE), La Trobe University, and Western Sydney University, and gives individuals and community groups the opportunity to participate in activities such as turtle habitat construction and restoration, turtle nest protection and fox management.

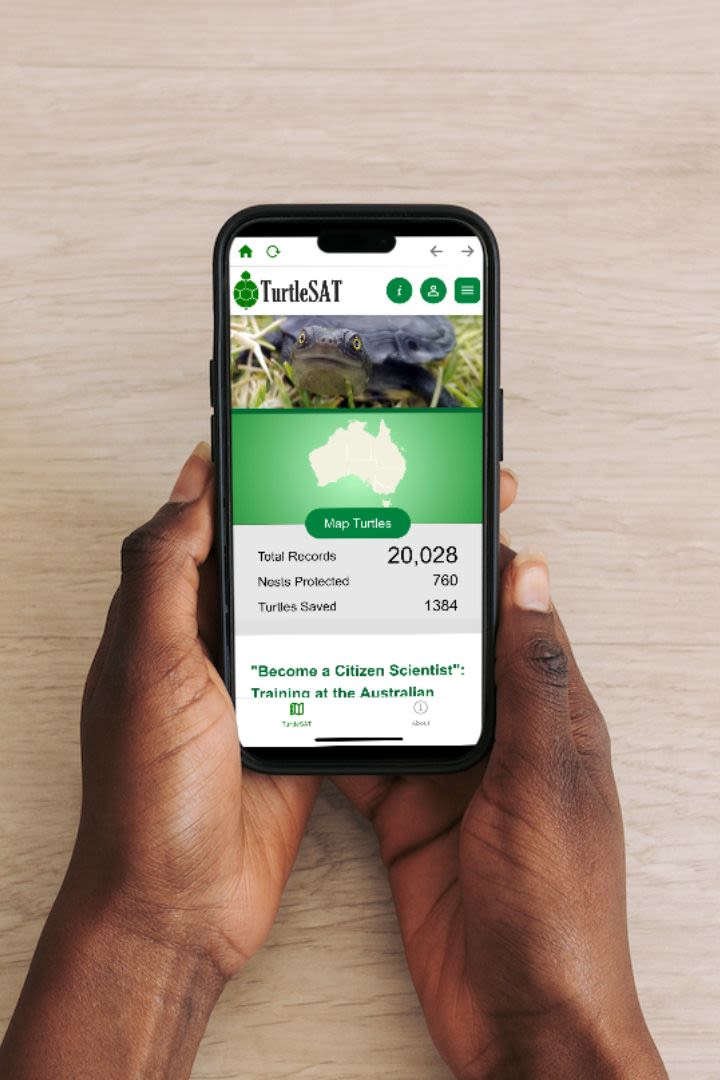

The TurtleSAT app is at the heart of the highly successful program and enables community members to record their sightings anywhere in Australia, with the data helping to reduce turtle deaths.

"It's not just Bell's turtles that need our help," says Lou.

"At this time of year, many eastern long-necked turtles come out of the water and nest around dams and creeks.

"Many also take advantage of the wet conditions to nest further afield or relocate to a different body of water.

"Sadly, lots of them end up getting squished on our roads.

"Help our turtles by slowing down, especially during or after rain, and keep an eye out for turtles crossing the road.

"If you do see a turtle on the road and if it is safe to do so, carry it across the road (in the direction that it was travelling) and let it continue on its way."